Good Times Bad Times: The Art of Roy Ferdinand

By Tony Sinn

January/February 2001

I’ve only lived in New Orleans for three years, and I’ve had good times and some bad ones, too. Sometimes I wonder: what kind of good times and bad times might someone see if they’ve lived in this city their whole life?

I’ve only lived in New Orleans for three years, and I’ve had good times and some bad ones, too. Sometimes I wonder: what kind of good times and bad times might someone see if they’ve lived in this city their whole life?

Artist Roy Ferdinand has apparently seen more of both than most anyone could imagine. I truly appreciate seeing New Orleans through his eyes, and having a chance to experience Roy’s life through his easy manner of expression, visually and verbally. I met Roy at his current residence, a place called Responsibility House, a year-long alcohol and drug abuse rehab program. Residents initially attend daily AA or NA meetings; a second phase requires finding a job. A month into the program, Roy was working on a drawing that he said would be his last related to drugs or the drug culture.

“My counselor said it would be a good idea if I did a piece that was my visual interpretation of addiction,” Ferdinand explained. His drawing shows a gaunt naked woman with her legs crossed in the lotus position. Needle marks cover her arms and various drugs and paraphernalia lay strewn in front of her. So this is Ferdinand’s final visual interpretation of addiction: the pills, the bong, the snort, the rock, the sex, the pain, the allure, and the death, which you can choose to see or ignore as a participant in the drug culture. Like a cross between erotica and a horror show, his naked woman looks sexy but dead, and I wondered where such a vision came from.

“My counselor said it would be a good idea if I did a piece that was my visual interpretation of addiction,” Ferdinand explained. His drawing shows a gaunt naked woman with her legs crossed in the lotus position. Needle marks cover her arms and various drugs and paraphernalia lay strewn in front of her. So this is Ferdinand’s final visual interpretation of addiction: the pills, the bong, the snort, the rock, the sex, the pain, the allure, and the death, which you can choose to see or ignore as a participant in the drug culture. Like a cross between erotica and a horror show, his naked woman looks sexy but dead, and I wondered where such a vision came from.

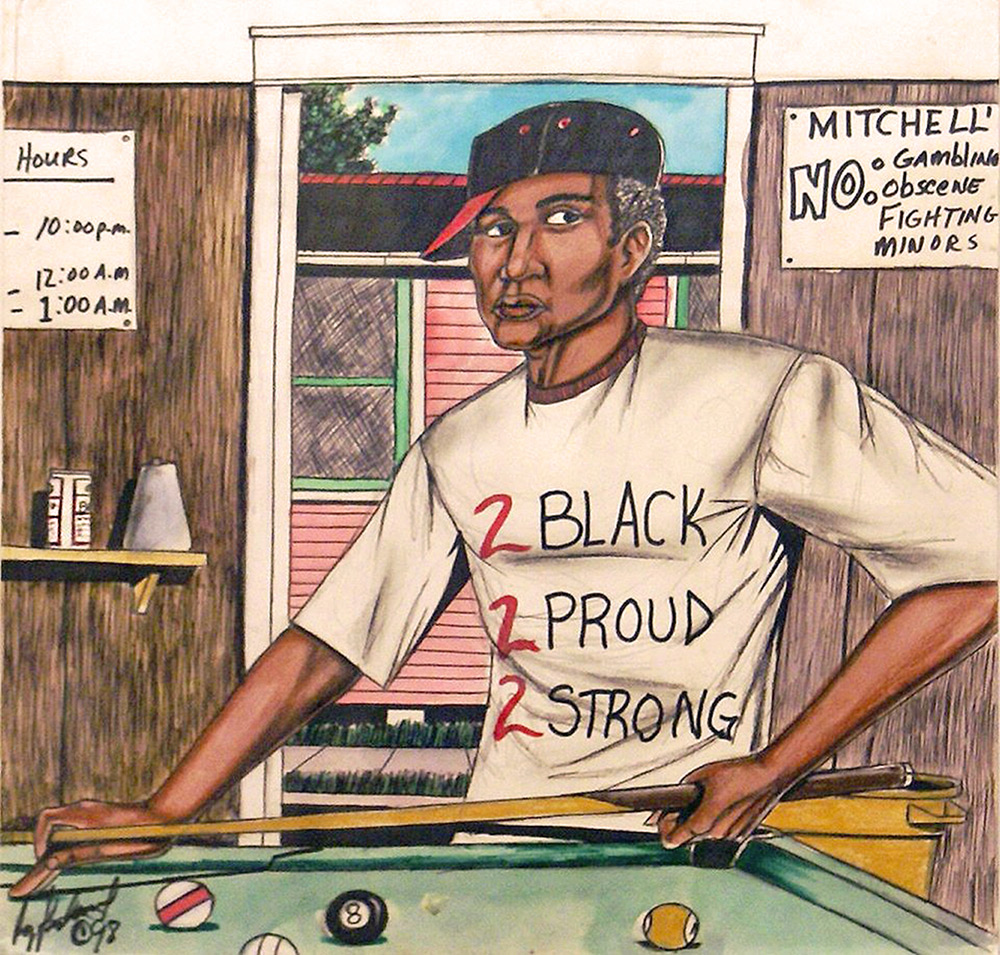

Known as “Cowboy” because he often wears a cowboy hat, boots, and spurs, Ferdinand has much to say about life on the backstreets of New Orleans. Roy explained that when he started drawing his stark scenes of street life, he undertook an “in depth study.” Often his subjects are a curious crowd of street people, some of apparently dubious character, chronicled in large, colorful drawings with a cool wit and great attention to detail. Roy paints what he sees, and he’s seen a lot, not always pretty or happy but always real. Though sometimes disturbing, his images are done with much love. Based on his close observations, Ferdinand’s art imitates life—as does most art—but he adds that in his case, “My own life started imitating my art—that’s why I’m in Responsibility House.”

He entered rehab after realizing that many people he’d known in the drug culture are dead, and deciding that he wanted to live awhile longer. “Unlike a lot of people in that life, I did have my fun, but I saw all that I needed to see, and I wanted to be a witness, not a casualty.”

He entered rehab after realizing that many people he’d known in the drug culture are dead, and deciding that he wanted to live awhile longer. “Unlike a lot of people in that life, I did have my fun, but I saw all that I needed to see, and I wanted to be a witness, not a casualty.”

Two and a half years ago, Ferdinand had his own close brush with death, when he nearly died on the street from undiagnosed stomach cancer. He survived with emergency surgery, but rumors in the art community held that he only had months to live. Indeed, some people apparently believe that Ferdinand is already dead, evidenced by a recent visit at Barrister’s Gallery (where Roy sometimes minds the shop) by an out-of-town art collector: “This dude came in and he started checking out my work, and goes ‘Isn’t this guy great?’ So I go, yeah, he’s pretty cool. The he says he would have loved to have met this guy, too bad he died. So I look at him and say, ‘Beg your pardon?’ Then he tells me that Roy Ferdinand died a few years ago, and wonders why I don’t know that, since we’re selling his art work. He goes, ‘Where you been, man?” So I told him, ‘Well, apparently I’ve been dead.’”

Ferdinand’s illness made his drawings a hot commodity in the art world. “F’ing vultures,” is his half-humorous assessment of that turn. “These are the guys who when I went around to sell my art, they said they didn’t have any money, but now they think I’m almost dead, so they want my work. Let’em pay museum prices for it.”

Ferdinand’s illness made his drawings a hot commodity in the art world. “F’ing vultures,” is his half-humorous assessment of that turn. “These are the guys who when I went around to sell my art, they said they didn’t have any money, but now they think I’m almost dead, so they want my work. Let’em pay museum prices for it.”

Ferdinand will soon have to find wage-earning employment, required by his residency at Responsibility House. “I told them that I’m an artist, but I have to get a real job,” he explains. “I’d like to get a job with the Orleans Parish Prisoner Art program, but don’t know how I would deal with working in a prison. I just have a problem going into a prison, be it voluntarily or involuntarily.”

In the meantime, Roy Ferdinand is still making his art, offering a glimpse of a world unfamiliar to most, but a stark reality for his subjects. While showing us specific street corners in New Orleans, Ferdinand’s art finds themes most of us can relate to, fear, lust, beauty, tragedy, and finally hope. Roy Ferdinand’s work can be seen at Barrister’s Gallery, 1724 Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in New Orleans.

In the meantime, Roy Ferdinand is still making his art, offering a glimpse of a world unfamiliar to most, but a stark reality for his subjects. While showing us specific street corners in New Orleans, Ferdinand’s art finds themes most of us can relate to, fear, lust, beauty, tragedy, and finally hope. Roy Ferdinand’s work can be seen at Barrister’s Gallery, 1724 Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in New Orleans.